Cathars, Pyrenees’s Good-Men.

Cathars, Pyrenees’s Good-Men.

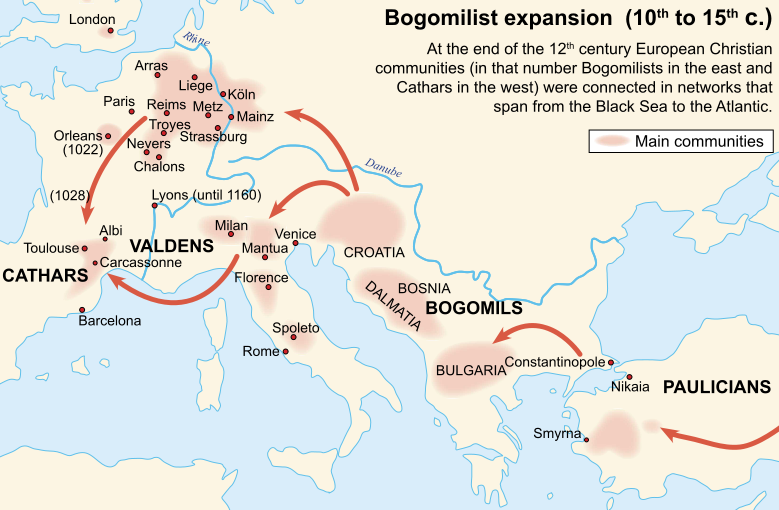

Catharism was a gnostic Christian movement, spread from the 10th to the 13th centuries, throughout Asia Minor, the Balkans, northern Italy, Occitania, Rhineland, Champagne and the Pyrenees. The emergence of Catharism in the Rhineland was called catiers, referring to the allegations that the devil was worshiped. Since this was a rude term, the Cathars often called themselves Pyrenees’s Good-Men..

The Cathars believed in the New Testament and had a dual worldview. They based in the idea of a good God that dragged good souls to heaven and evil ones to hell, which is this world.

The Cathars did not believe in saints or dogmas. They rejected the economic imposition of Roman-Catholic believers. The women were in charge of managing houses, while men were leading a wandering life, preaching God’s message. They rejected of the material world, which they believed was created by the Devil, led them to advocate the ideals of poverty, chastity and vegetarian nutrition. They were against the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church too.

The salvation was achieved through gnosis and ascetic practice, rather than thanking Divine grace. They believed that people who had died didn’t enter heaven and were reincarnated to redeem theirs sins. The Cathars were characterized by building their own Church system, with sacraments, faithful followers, and clergy. The Catholic Inquisition considered organized a hierarchy of bishops for them whose job was to spread, through preaching and the example of poverty, the doctrine among the faithful.

Catharism in Occitania.

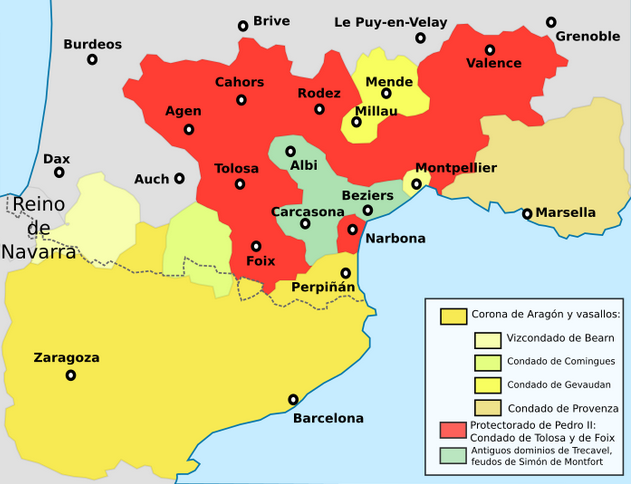

The Cathar Church was established in southern Gaul and Lombardy, with its structure of bishops, in Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne, Agen and Lombardy. They held a Cathar council in 1167, in Sant Félix de Caramany, not far from Toulouse.

In France and Rhineland, Catharism wasn’t consolidate due to the determined anti-heretical reaction of the Roman Catholic Church. At this time, in Soissons, 100km northeast of Paris, a crowd stormed the prison where some peasants, suspected of heresy, were locked up, and ready to be lynched. In Occitania, however, there wasn’t any control regarding Cathars being heretics.

In this situation, many French Cathars, Flemish or Rhenish, migrated to the south in Occitania and Lombardy, where the Cathar Church acted freely.

The situation in Occitania and North-Catalonia.

In Occitania, to the north toward France, the appointment of roman-christian bishops was achieved without the intervention of the laity. The Pyrenees’s Good-Men. spread their power to the people. When a large family decided to entrust a daughter to a religious institution for upbringing, they had to resort to the Cathars. Additionally, women could also be clergy. Grand Lords were in constant strife with Roma’s bishops. In this way, the count of Foix, who was conflicted with the abbot of Pamies, disputed the control of the tithes of the parishes in their dominions.

The diocese’s land of Toulouse was an immense territory, which the bishops could not control due to a lack of means; the Lords monopolized the tithes of the parishes.

Thus the Toulouse’s power disintegrated. The Catalonians and Aragon Count Ramon V, faithful to Roman Catholicism, asked for help in combating the heresy of their domains. In fact, some cities had become communal regimes, such as: Toulouse, Carcassonne, Montpellier, Narbonne and Nimes. They protected all their inhabitants, even though they were heretics.

In this context, Catharism took root in Occitania and expanded to Garonne and the Pyrenees, reaching Catalonia, from Urgell, to Berga, Lleida and the Priorat. In Occitania and northern Catalonia, the Cathar Church operated with complete freedom, and its adherents could integrate without any problem during the 12th and 13th centuries.

“Peaceful” efforts to combat heresy.

The coexistence of two Christian church-systems in Occitania was usual, but political and ecclesiastical powers considered it intolerable. Considering that they were a Roman-Christian country where heresy was not condemned, King Peter II (a Catholic) of Catalonia and Aragon, decreed measures against the heretics in 1198.

Forty years of crusade against heresy and the Beziers massacre.

The Occitan region of the Toulouse Lord and the land of Lord of Trencavels were at the height of their culture. They had nothing to do with regions of northern France. The French monarchy and the Pontificate saw Catalonia and Aragon expansion in Occitania as a threat to the balance of powers, so they organized a crusade, with the pretext of a Cathar confession.

In 1200, the Lord of Toulouse Ramon VI got married with Elionor from Aragon. Elionor was a sister of Peter II the Catholic, King of Catalonia and Aragon.

Shortly afterward, the newly married Peter II, the Catholic, went to Rome where Pope Innocent III crowned him, thus becoming a vassal of the Holy See. Peter II promised to pay tribute to the Pope. With this gesture, Peter II the Catholic sought to protect his dominions from a possible crusade. The Pope, wary of the Catalan king’s attitude toward the Occitan Lords and suspecting him of tolerating heresy, never wanted to grant him the crusade against the Cathars. In response Peter II the Catholic, by himself, took action against the Pyrenees’s Good-Men..

In 1207, while Innocent III was setting up the crusade against the heretics of Pyrenees’s Good-Men., the Pope issued a sentence of excommunication against Ramon VI, because the Count of Toulouse had not accepted the statutes of peace. In this tense situation, in 1208, the murder of the papal legate, Peter de Castelnau happened. Then Philip II, the King of France, organised the crusade and designated Simon de Montfort as leader. Simon used methods of torture to exterminate the Cathars.

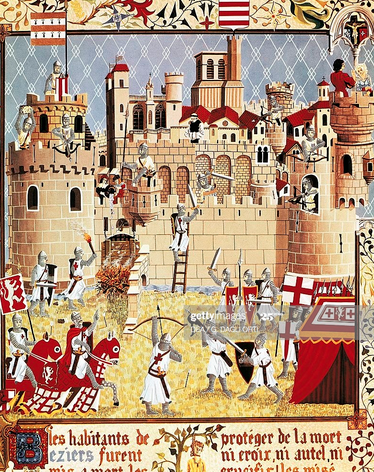

In spring 1209, the crusade armies, of the French barons, reached Lyon. Count Ramon VI, in order to prevent an attack of his domains, mobilized those obedient to him and took part in the crusade. In July, the Crusaders besieged Beziers, perpetrating a big slaughter, even Roman Catholics. The Pope legate said, “Kill all them. God will distinguish theirs”. Twenty thousand men, women, old men and children were killed in the siege, when all were refugees in the church. This was the first “genocide” in the modern history. The show of gallows and bonfires, with streets flooded with blood, was ghostly.

Following the massacre of Beziers and its inhabitants exterminated, other cities surrendered without fighting. Except Carcassonne, which, besieged, had to surrender due to a lack of water. Then the Crusaders forced Pyrenees’s Good-Men. to leave the city and the soldiers began acting against those who didn’t leave, condemning them to die at the stake.

Pyrenees’s Good-Men and The Muret’s battle

On February 1211 during the Council of Montpellier, the Pope’s legacy Arnau d’Amaurí, prevented reconciliation and imposed on Count of Toulouse very hard conditions, having him emigrate to the Holy Land. Instead of that, Ramon VI came back to Toulouse and expelled Bishop Folquet. Then Simon de Montfort besieged Toulouse, but had to retreat due to the resistance of the city. Afterwords, Ramon VI, Lord of Toulouse and Counts of Foix and Comenge, asked for help from the Catalan-Aragonese king, Peter II the Catholic.

Because of context of political and religious conflict in Occitania, king Peter II the Catholic, with feudal liabilities towards his owns Counts and never tolerant with heretic Cathars, began reconciliation measures in order not to lose his power in the country. Thus, he took over the castle of Foix on the proviso of delivering it to Simon de Montfort Prelate Papal, as long as the count of Foix pledges allegiance against the Roman Christian Church.

Simon de Montfort, rejected again conciliation in the synod of Lavaur. So, Peter II the Catholic declared himself a protector of all Counts and Lords in Occitania, including the Toulouse municipality. This decision caused an armed confrontation, resulting in the Muret’s Battle (1213), in which Peter II the Catholic, defender of Ramon VI and the Occitan Lords, was defeated and killed. In the fourth Lateran Council (1215) the Pope recognized Simon de Montfort as count of Toulouse, and divested Ramon VI, who went into exile in Catalonia.

Following the defeat of Muret, the Pyrenees became a closed border for the Catalonia and Aragon crowns. Therefore the only possibility for expansion of this kingdom was to the south (to Valencia) and through the Mediterranean (to Mallorca) led by the son of Pere II (Jaume I The Conqueror), James I was delivered to Simon during the Crusade as a pledge of the future wedding with his daughter, but this is another story.

Heresy’s end, castles destroyed and death at the stake.

The king of France always had Papal support, because he guaranteed the removal of heresy. In 1244 the Montsegur’s castle was used as a refuge for the last persecuted Cathars, Pyrenees’s Good-Men. The last big battle took place here; many believers of the dualistic faith died there; others escaped through the Pyrenees to exile in Catalonia. A legend tells that in this castle there was a treasure, this treasure could be the Holy Grail, it is said that the Prefects of Montsegur escaped from the siege by secret passageways.

With the fall of the last Castle of Queribús, the crusade against the Good-Men ended. The castle of Perapertusa (in Occitan “open stone”) accepted the submission to the royal troops after the Carcassonne siege, but Perapetusa wasn’t listed in the Pyrenees Treaty on 1659. Catharism was considered eradicated with the capture of William of Belibasta (1321); he was the last known Cathar reverend.

Charlemagne and his descendants didn’t like the relationship between Occitanía and Catalonia and Aragon. So they made some unsuccessful attempts to marry off daughters of France’s king with kings of Catalonia and Aragon, in order to recover dynastic rights over southern France.

Since that time, the inhabitants of the ancient Cathar, Pyrenees’s Good-Men. cities have great sympathy for the allies that assisted them in their attempt to be Cathars, in a world in which the ideology of the Roman Pope prevailed.

The Occitan Cross.

The Occitan Cross is a Christian symbol that was adopted in the Occitan land. Nevertheless this cross appeared already in many pre-Christian tombs. Cathars adopted it on its flag with the four red-bars of Catalonia.

The Cathars, Pyrenees’s Good-Men, gave up symbols of idolatry, particularly the Occitan cross’s association with the solar world and the twelve symbols of the western horoscope. Therefore Counts of Toulouse adopted this symbol as part of their heraldic shield in the thirteenth century. Over the years it was accepted as a heraldic-nobility symbol.

Pyrenees’s Good-Men Family curiosity

My family-name Sauret comes from southern France. Andreu Sauret traveled from a village named Fos in the French Pyrenees. Andreu got married to Margarita on 1675 in Catalonia. I’m their seventh generation descendent. I have always associated the history of the Cathars with the origins of my family. Although there isn’t an exact relation, time wise, it might well be related to some migration from the French lands to Catalonia. So I dedicate this article to men and women who lost their lives at the stake defending beliefs that fostered their lifestyle.

BarcelonaWalking Barcelona Hiking Barcelona Montserrat Costa Brava Pyrenees

BarcelonaWalking Barcelona Hiking Barcelona Montserrat Costa Brava Pyrenees